Bringing Design to Life

The Bauhaus: or, How a Short-Lived School Shaped a Century of Design, Part I

Introduction

What connects the gleaming skyscrapers in the core of our cities, the sleek surfaces of our computers, the bold colors and provocative forms hanging in the MoMA exhibit of Abstract Expressionism, and Gen Z’s tendency to omit capital letters?

In the early 20th century, an art school emerged in Weimar, Germany, that brought together potters, architects, painters and writers. This assemblage would exist for only a brief period, yet during that time its professors and students incubated the theories and aesthetics that would come to dominate every area of artistic production over the next 100 years, and eventually characterize design in every facet of our daily lives. This school was the Bauhaus.

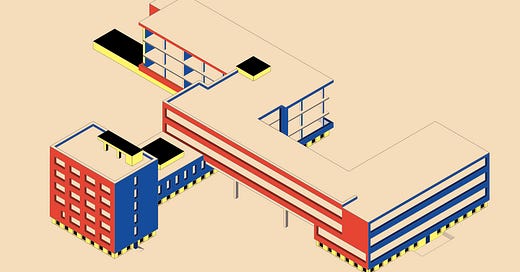

The most direct, lasting, and important of the Bauhaus's influences was the buildings we live in. The skyscrapers that have become the archetype for modern vertical architecture were conceived at the school before being built in New York in the 1950s and 6Os, primarily through the influence of Mies van de Rhoe.

At the same time as the school was shaping our new spaces for living and working, it was also transforming our way of seeing. The early Bauhaus artistic directors Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee offered a new approach to the visual arts decomposing colour, shape, and form—a process that culminated in the works of Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock.

But the school's impact was not limited to expensive architectural practices or the elite institutions of professional art. The Bauhaus also shaped the progression of all modern printing and graphic design, creating some of the first modern sans serif typefaces and championing a ‘New Typography.’

All of which is to say nothing of the impact the school had on furniture, photography, and Apple products.

The Bauhaus haunts us to this day, often where we might least expect it. Such a singular influence deserves an explanation. How did this German arts and crafts school founded in 1919 in a beleaguered and defeated Germany, and shut down less than 15 years later by a Nazi purge of 'subversive' art styles, achieve such dominance? Was there anything special in their methods that drove these effects?

The answer is a story of philosophical idealism, practical discipline, and an intense focus above all else on craft. The Bauhaus, under the influence of the German Kindergarten system and the Arts and Crafts movement in England, sought to merge theory and practice with a new approach to design centered on the building as a gesamtkunstwerk—a “total work of art”.

Through the skill of the people that it trained in this method, the Bauhaus became the vital engine for the whole field of modern design. However, this liveliness did not ensure that the work they created would be loved. The Bauhaus stylistic record is mixed at best, with their buildings often described as "sterile" and "inhuman", or a field of "glass boxes". Nonetheless, their importance is irrefutable.

If we wish to create an alternative design language for our world, or achieve anything like the same degree of lasting, multi-dimensional impact to the way people approach the arts, we must understand their work. In Part I, we’ll consider how this group’s holistic approach to their craft allowed them to create a new kind of artist with a new philosophy of art. In Part II, we’ll consider how those artists applied that new philosophy to exert an outsized influence on the modern world.

The Beginnings

"Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist" – Walter Gropius

The Bauhaus emerged from the reconstruction of Germany after the First World War, when the German government sought to create a new institution to train the next generation of builders. To lead this institution, they turned to a rising star of architecture in the country, Walter Gropius. Gropius came from a storied architectural lineage: his father was considered a great architect, and it was clear from a young age that Gropius would follow in his footsteps. Yet it was equally clear that he was looking for something new.

Gropius was keenly aware of the importance of craftsmanship and technical skill. When traveling in Spain at a young age, he was exposed to traditional tile manufacture in Catalonia, which, as he wrote in his journal, “instilled in him a great admiration for the intricacies of good craft work in any kind of material". During his training at an architectural practice, Gropius also studied the Arts and Crafts movement in England, an anti-industrial group that "aimed to eliminate the distinction between free and applied art, finding inspiration in the shapes and colors of nature, in Mediaeval Europe – and in Japanese art".

When he was asked to take over the Grand- Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts, Gropius saw his opportunity to put into practice his incipient theory of architecture and education. He insisted on combining the School with the Fine Arts Institute, explaining, "the principle of training the individual's natural capacities to grasp life as a whole ... should form the basis of instruction throughout the school instead of in only one or two arbitrarily 'specialized' classes".

The new school was called the Bauhaus ("house of building"), imagined as a modern version of the medieval stonemasons guild, the Bauhütte. It would be a "collaborative group of artists of all disciplines united in constructing a new and better world".

The Bauhaus Program

"What we preached in practice was the common citizenship of all forms of creative work, and their logical interdependence on one another in the modern world." – Walter Gropius

Gropius would eventually crystalise the aim of the Bauhaus as the production of a gesamtkunstwerk—“a total work of art". As he put it in the opening lines of his 1919 manifesto that launched the school's program,

The ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building! To embellish buildings was once the noblest function of the fine arts; they were the indispensable components of great architecture. Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, cooperative effort of all craftsmen. Architects, painters, and sculptors must recognize anew and learn to grasp the composite character of a building both as an entity and in its separate parts. Only then will their work be imbued with the architectonic spirit which it has lost as “salon art.”

In other words, a building should contain thoughtful products from every art and craft involved in its construction to live up to its potential.

Originally, this kind of cooperation between the arts was the default. Painters, sculptors, and architects would naturally collaborate on every work they completed. However, with the rise of "salon art", museums, fine art, art history, and art theory, the different arts had started to be treated as independent units that could be worked on, and even perfected, separately from one another. The aim of the Bauhaus was to bring them back together. At first, this meant consciously designing the furniture, visual art, sculpture and other natural aspects of the built form. Over time, though, as the school continued, this would expand to include advertising, commercial endeavors, theater, music and even political reform to influence the society in which the building was created.

To create a total work of art required a total artist. The Bauhaus recognised that a building was always a matter of collaboration between multiple artists, but they reasoned that managing that collaboration would require a holistic understanding of the arts involved, at least by the primary architect. This meant not only a theoretical knowledge of the various parts of the building, but also the ability to marry that theory with practice. The skill of academically trained people was, in Gropius's words, "amateurish studio-bred order which is innocent of realities like technical progress and commercial demand". Instead, the Bauhaus sought to create competent architects who could get things built, and the entire curriculum was structured with this aim in mind.

New students at the school signed on as 'apprentices' of a multi-year program that included both classroom education and working on real world problems. The first step was a six-month preparatory course developed by Johannes Itten, who had previously been a teacher in primary and secondary schools. The course was inspired by the Kindergarten movement, where children were "educated with a routine of craft-based, geometrically pure manual exercises". During the course, "Practical and formal subjects were taught side by side so as to develop the pupil's creative powers and enable him to grasp the physical nature of materials and the basic laws of design". In this way, the course was something like what you would expect from joining a Shaolin temple or learning karate at Mr. Miyagi's shop, a space to inculcate a beginner's mind for design.

Following the preparatory course, the next three years focussed on training the specific skills that students would need in the construction of a building. Courses covered practical instruction in materials and tools, formal instruction in the theory of architecture, and more abstract design concepts such as volumes, colors, and composition. Students would receive instruction on everything from textiles to bookkeeping to gain the holistic set of skills that the Bauhaus vision demanded.

At the end of this training, students graduated to become Journeymen, which allowed them to work on real building projects. Journeymen would continue with a mix of on-site and research work until they received a diploma.

Having a course structure modeled on apprenticeships was ideal for the Bauhaus. It allowed them to create a holistic program covering all aspects of the building, while creating plenty of space for the picking up of tacit knowledge. Again, as Gropius put it, "The best kind of practical teaching is the old system of free apprenticeship to a master-craftsman, which was devoid of any scholastic taint".

Craft in a World of Machines

“Were mechanization an end in itself it would be an unmitigated calamity, robbing life of half its fulness and variety by stunting men and women into sub-human, robot like automatons.” - Walter Gropius

Yet this eagerness towards the adoption of craft was not without its anxieties. At the time that the Bauhaus was operating, concerns about the impact of mechanization were pressing. Recent generations had experienced a rapid industrialisation, and the First World War had convinced many that these industrial capabilities would transform the world. There was a prevailing assumption that the economic superiority of factories and mechanization was undefeatable, and that these methods would come to dominate all areas of production.

The Bauhaus grappled with this situation through their emphasis on what Gropius called "standardization". For Gropius, it was clear that "the machine is the modern medium of design". So, as the Bauhaus training program progressed, it emphasized the use of machines in the creative process, and every student had to work for a time in a factory. The hope was that if the factory form of creativity was understood, it could be improved, to emphasize the process of craft rather than subsuming craft under its economic might.

This, then, was the program: an apprenticeship aimed at creating architects that had both a theoretical and practical knowledge of all the arts needed to create a building. It began with bottom-up training in the forms and methods of architecture and continued until the apprentices could take on almost any artistic role required. Throughout this training, there was an emphasis on standardization and the deployment of the arts in an increasingly mechanized world.

We'll return to the impact of this final aspect of the Bauhaus approach on their buildings in Part II. But for now, we can note that this knowledge of the factory and the impact of mechanization meant that the students of the Bauhaus were fully prepared to make use of these factory techniques, including the resulting scale, in their final works—whether they be buildings, furniture, advertising, or something else.

This kind of preparedness was an essential aspect of the Bauhaus program. Upon graduation, the student had developed practical skills that could be deployed to create art in multiple domains, but also the ability to cross-pollinate ideas between those domains. When you have worked on a particular problem in the real world, it gives you new ways of seeing that problem that are not obvious to those who have simply studied those problems in a classroom setting. In The World Beyond Your Head, Matthew Crawford describes this as a ‘disciplining’ of attention:

“When we become competent in some particular field of practice, our perception is disciplined by that practice; we become attuned to pertinent features of a situation that would be invisible to a bystander.”

Through the marriage of practice and theory, students of the Bauhaus had experienced exactly this kind of disciplining to see new aspects of the problems they attended to. Uniquely, though, as a result of the school’s multi-modal training, this deepening of attention was matched by a breadth of attention that could take in all of the components of a design. It was this combination of breadth and depth that made them shockingly effective.

As we’ll see in Part II, such effectiveness was not simply theoretical. By translating their skills across disciplines and using heuristics learned in one place to shape another, the Bauhaus were able to influence a huge variety of objects and have a lasting influence on design throughout the 20th century and into the 21st.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Robert Bellafiore and Brian Hagood, for reading early version of this essay.

All of the quotes for the section headings are from Gropius’s manifesto The New Architecture and the Bauhaus. I found the ABC’s of Triangle, Square, Circle: The Bauhaus and Design Theory particularly helpful for understanding how education at the school operated.

Part II looks at the wide-ranging and lasting influence of the Bauhaus to understand just how this method of training translated into impact, as well as taking a closer look at the ways such impact may have been misguided. The Long Shadow of Modernism

In Part I, we looked at the unique methods the Bauhaus used to train the next generation of architects in pursuit of the building as a ‘total work of art’. In Part II, we’ll look more closely at the school’s influence and ask whether the application of those skills amounted to a better style.