Growing up I had very few opportunities to work with my hands, and even fewer to create things that would actually be useful in my day-to-day life. I got interested in art, and for a brief period tried sketching and pencil drawing, and I also vaguely recall once completing a balsa wood box as part of a school crafting project. But, beyond that, the main way I developed my hand-eye coordination was through video games. This meant that by the time I became a responsible adult I was far from "handy". I remember being in my early twenties, picking up a piece of lumber that I needed for a DIY project, and feeling lost. The weight, texture, and toughness were all completely foreign to me. For what seemed like such a 'basic' activity it was surprisingly overwhelming.

Since then things have improved, I have managed to participate in wiring lights, landscaping gardens, and even removing and reaffixing a door. I am still not a person that could describe themselves as particularly resourceful but I can think seriously about doing a DIY project before dismissing it. This journey required a strong dose of trial and error but the fundamental reason I have been able to do this is YouTube videos. Without YouTube as a resource most of these projects could never even have been attempted.

This experience, though perhaps a little extreme in the distribution, is not out-of-place today. Concrete data on DIY activity in the US is hard to come by. However, it is clear that over the last seventy years the institutions that teach the foundational skills of DIY, everything from woodworking and car repair to gardening and sewing, have been in terminal decline. It also appears from survey data and anecdotal experience, although the evidence is not one-sided, that young people feel less capable than previous generations. Nonetheless, at the same time, according to the most concrete data available, the sale of home improvement equipment, interest in DIY projects has never been greater.

What accounts for this mix of trends?

Over the last hundred years the mediums we traditionally used to teach manual skills - apprenticeships and schooling - have atrophied. First as a result of progressive formalisation, and then by active reprioritization. However, over the same time period, YouTube and similar services, have given people access to knowledge about how to complete complex DIY tasks in ways that would have been impossible in any previous medium. This has meant that even as formal education mechanisms and direct intergenerational skill transfer have declined it has been compensated for by a new ecosystem of informal teachers.

However, the impact of this transformation is uneven, with both promising advancements and meaningful drawbacks. Although YouTube is a powerful new avenue to learn mechanical skills, it still falls short of covering the essential elements that a comprehensive training program could provide. There are some experiments happening to expand the scope of novel DIY education to account for this with things like Makerspaces and craft kits. But, it is still early days, and even with these products we are unable to address the most pressing issue. The reason we let the education of manual skills degrade is because we have come to value this kind of labour less. If we think that the wisdom of our hands is important and not something idly tossed aside then we should look much more closely at how our society values and trains these skills.

The History of Handiness

“It is by having hands that man is the most intelligent of animals.” - Anaxagoras

A just-so story of the early history of manual skills might go something like this: At first, most groups of people (tribes, family units, clans etc.) were fully responsible for producing all the goods that the group needed: homes, furniture, clothing etc. There was perhaps some minor specialization within each group and irregular trade further afield but for the most part everyone ‘did it themselves’. As the economy developed, and different groups became interconnected, specialization accelerated and specific jobs associated with particular crafts began to develop.

This specialization was associated with technology improvements and meant more sophisticated skills were required to create end products. Under such an economic model craftsmen needed to find ways to train the next generation to expand and continue their business lines. As we've seen, one of the first mediums that developed for this training, as an augmentation to standard intergenerational transfer, was apprenticeships.

Over time though, as specialization continued and industrialized society developed, training for these skills became still more formalized. Shop classes were created to begin training all school-goers from a young age, and vocational colleges were setup to offer the final stage of formal education that could allow someone to take on a craftsmanship role. These institutions lacked the holistic skill transfer of apprenticeships and intergenerational training but they still ensured that there was a broad based understanding of manual skills across the population.

In the last 50 years though, even these institutions have started to erode. Following WW2 there was an increased focus on four year colleges as the pinnacle of education with special emphasis on having returning servicemen enter college as part of the G.I. Bill. These efforts continued up to the present with other legislation like the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act and have led to a prioritization of formal and testable skills like maths and reading at the expense of shop class and similar education in manual competence.

Why is this a problem? There are existential reasons that a lack of manual competence can be damaging to a society. DIY work has a unique ability to put us in touch with the world, to gain a visceral sense for what it takes to create something good, and to be humbled by that experience. "In our attempts to craft useful beauty, what we are also crafting is ourselves"1.

But, even at a functional level a loss of these skills brings with it serious risks. Under a classic free market economic perspective the kind of specialization is not a major issue. The market forces will naturally lead people to specialize and then trade between them will solve for any relative inability to receive a particular good. Certainly this has held true in the abstract. Despite a lack of formal education for manual skills we experience greater material abundance now then at any point in the past. The issue though is that this abundance has come at the cost of fragility.

Any person, city, or country, requires a large set of capabilities across different domains to be able to deal with the variety of challenges that can emerge in a complex world. You can see an example of this in your own body. If another person were to attack you on the street you could use your arms and legs to fend off the attack or at least run away. But, if instead you were to catch a cold then you would rely not on your arms and legs but on your immune system to fight off the virus. Without both of these requisite capabilities you would be too weak to face the wide range of challenges that the world presents.

In cybernetics a system that displays this kind of complex set of capabilities is said to have multiscale requisitive variety In the exact same way our body needs multiscale requisitve variety to deal with all the problems that could assault it, our society needs multiscale requisite variety to be able to deal with any problems that could come up. It has been pointed out now many times, but this was made clear to everyone by the supply chain break downs that happened during COVID.

In a clean economic model issues like this would be naturally corrected for by the market by diverting people from one area of production to another. But, skill sets are not fungible, and once lost they are not easily replaced:

"An art which has fallen into disuse for the period of a generation is altogether lost. There are hundred of examples of this to which the process of mechanization is continuously adding new ones. These losses are usually irretrievable. It is pathetic to watch the endless efforts - equipped with microscopy and chemistry, with mathematics and electronics - to reproduce a single violin of the kind the half-literate Stradivarius turned out as a matter of routine more than 200 years ago."

Personal Knowledge, Michael Polanyi

One way you can understand this is by imagining what would happen if there was a sudden boom in house construction but a severe shortage of good framers. The classical economic model would say that this situation would lead to many people switching into framing from other careers and the problem would be solved in short order. But learning complex skills, especially ones which require a lot of tacit knowledge, is not so simple. It may be possible for a framer in New York to write down the steps needed to install a new door frame but is this sufficient for someone in Miami to successfully complete their own installation? The system may eventually correct, but in the meantime there will be real economic hardships.

Luckily however, it appears that we may have a saving grace from new technologies that have made this issue slightly less pressing.

Digression: What does it look like when millions of people suddenly need a desk but you can't buy a desk?

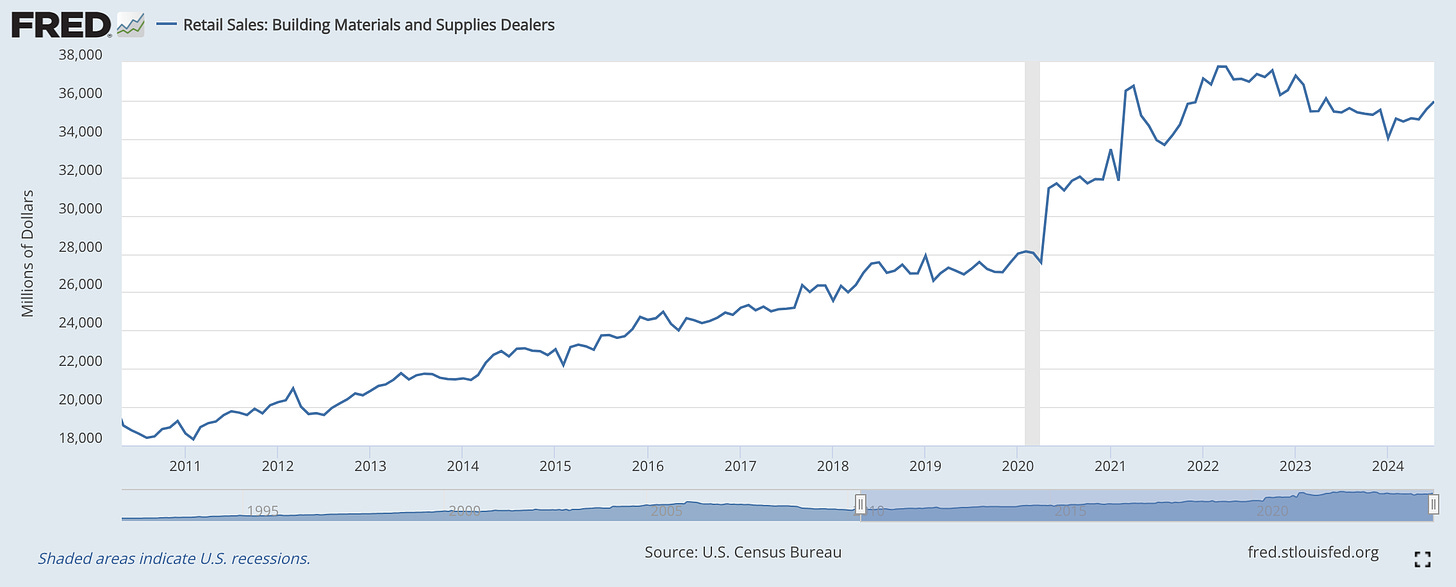

During the COVID-19 pandemic there was a boom in home improvement projects. As people were confined to their homes and unable to travel or work elsewhere there was, over a very short period of time, both an intense interest in improving home space as well as time to actually make the improvements. Overnight there was a significant rise in searches for building products and an almost 15% jump in the sales of home improvements goods

Especially because they were stuck at home, there was no way for people to access traditional mediums to learn how to complete these projects. So, they turned to YouTube.

Searches for How To videos of every kind grew rapidly with a particular jump for videos associated with DIY projects. And through these videos, as well as some trial and error, millions of people began to muddle through what it means to develop manual skills.

How YouTube creates skilled craftsmen

Without trying to make too fine a distinction, there are roughly two types of YouTube DIY videos.

The first is the classic "How to" video that explains a specific task. Recently, I was looking into what it would take to switch the swing of a door in a new apartment. The current swing reduces the room's usable space and I wanted to see how hard it would be to flip it around. To do this I browsed a variety of "How to" videos like this one:

In a "How to" video the steps needed to complete a task are laid out with an accompanying video and commentary. This can be a super slick production like this example from B&Q, a home improvement retailer in the UK. Or, it can be a shaky handcam from a craftsman documenting a recent job. Usually the former will get you the basic information faster but the latter is the better source of education, even if it takes a bit more effort to digest. Either way, depending on the craft in question, it is rare to find a single video that has all the exact steps you will need to follow. Often you will have to combine different videos, and include some improvisation. But, through this collection there is almost always enough information to have a good starting position with a project.

The second kind of video I would describe as the "DIY influencer". These are individuals that regularly show their projects over time. These may follow a specific theme or even have detailed instructions on how a thing is created but there is no formal path through the videos that are posted and they are generally too specific to be of use in completing a specific job. The content remains educational but it focuses on projects that represent their 'brands'.

Because the content is more diffuse people will watch it less because they want to complete a particular project and more because they are generally interested in the craft on display. By watching a single influencer repeatedly across time you can learn how to be a good at a craft in a similar way to how an apprentice might watch a master craftsman as they go about their day and pick up skills by observation and imitation.

Of course these two categories are not completely distinct. DIY Influencers will often create How To videos and a How To video channel will regularly throw in something that looks more like a DIY Influencer post. But, it is these two kinds of education working in concert that makes YouTube so useful for picking up skills. By having explainer videos that can go into detail on particular tasks combined with a broader look at the ways that a top craftsman operates someone can receive a pretty holistic education in a set of DIY skills. Certainly, enough to build themselves a desk or cook a passable spicy chili garlic noodles.

But even with this combination YouTube does not present a complete solution to teaching manual skills. A YouTube video remains a disembodied artifact. You may be able to learn all the steps needed but when it comes time to pick up tools and materials or find a friend to help you with a project you may find that the situation 'on the ground' lacks the things you need to succeed.

Moreover, although a video is a much richer medium then a set of written instructions, it is still a kind of formal education and there is significant tacit knowledge lost in the process of formalisation. A DIY Influencer in New York may now be able to show a video from multiple angles explaining how to frame a door. But for someone in Miami it's almost certain that, at least in their first couple installations, they will still be surprised at the ways they need to hold the wood to be able to set it up correctly or how humidity affects the wood over time. These and any other number of things are lost on a video but would have been clear if they had learned the skills in person and in situ.

Where do we go from here?

"There are websites for ‘weld porn’ and the mere fact that this is so should be of urgent interest to educators" - Matthew Crawford

YouTube has given people otherwise bereft of formal methods a way to learn foundational manual skills. It's hard to judge for sure, but this seems to have provided the DIY movement a new lease on life and helped to ensure a base level of manual competence across a new generation. However, there is much more that could be done. There are two major gaps in the medium itself that are starting to be addressed today: access to tools and materials, and in-person teaching.

Buying tools and materials can be overwhelming - as I experienced the first time I went to pick up lumber. The things you need may not be readily accessible and there is often just as much skill required to shop well as there is in the other parts of a job.

One way to get around this is following through a similar path to the one taken by the meal kit companies pre-configuring set packages of tools and materials that can rapidly prepare someone to start working. One example of this today is Glory Allan who prepare DIY sewing kits with everything someone needs - apart from the sewing machine - to get started on their first project.

To solve the transfer of tacit knowledge the most tried and true mechanism would be a return to in-person education. Scaling the apprenticeship model is great, as is expanding access to classroom education but we need more options for casual DIY hobbyists as well. Makerspaces like Toronto Crafts, which provides in-person classes on basic wood working skills, offer one promising avenue for this kind of learning.

Ultimately though we need to change what we care about. Although these new tools for learning manual skills are wonderful they can not, on their own, address the change in values that has occurred. If we want our societies to develop the variety of manual skills that are required to navigate our complex world then we must once again have people care enough to want to pick them up. During the pandemic a lot of people suddenly cared about these skills out of necessity. If we want them to keep caring now that consumer supply chains are again operating robustly we need to find more ways to integrate DIY practices into daily life. One of the most immediate paths we have to do this is by returning to a world where manual skills are once more presented as a prestigious and broadly available part of childhood education.

Not only would this help solve our society’s need for multiscale requisite variety but it may also help satisfy our souls. Learning how to use our hands to make things in the real world may go a long way to fixing some of the anxieties and the lack of attention that seem to plague our day to day.

“In schools, we create artificial learning environments for our children that they know to be contrived and undeserving of their full attention and engagement. Without the opportunity to learn through the hands, the world remains abstract, and distant, and the passions for learning will not be engaged.” - Doug Stowe

Acknowledgements

This essay is an experiment in a slightly more informal argument based on my observations of YouTube and skill acquisition. I also benefitted a lot from conversations with Glory Allan founder Andre Chin though all my conclusions are my own. Any feedback would be welcome.

The Wisdom of Our Hands, Doug Stowe

In Israel, there is a volunteer group called 'Yedidim", that specializes in jump starting cars and other types of non-medical' 'emergency' help.

They do a crash course on how to change a tire and stuff, but they're ethos is show up, and if you don't know then search on YouTube.